Loren R. Graham1

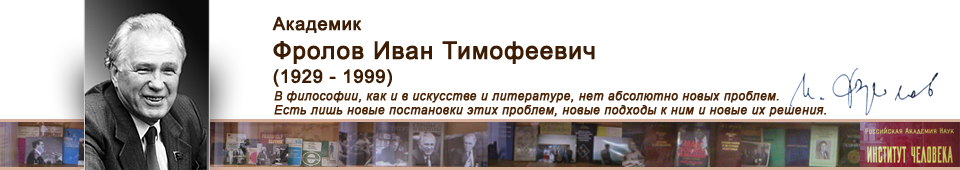

I.T.Frolov and the Soviet Philosophy of Biology

The healthiest period in Soviet philosophy of science during the last twenty years was from 1968 to 1977. During that time the editor of the main Soviet philosophy journal, Problems of Philosophy, was I. T. Frolov, the philosopher who made his reputation by writing a strong attack on Lysenkoist biology in 1968. Taking over the editorship of the journal at the peak of his popularity following his critique of Lysenkoism, Frolov set about refreshing Soviet philosophy of science by establishing closer ties with the rest of the scientific community. Because of his reputation as a philosopher who opposed ideological interference in science, he was able to arrange meetings between philosophers and leading natural scientists who in the past had usually stayed away from the dialectical materialists. The reports of these meetings, printed in the journal in a regular feature entitled “The Round Table”, changed the tone of Soviet philosophy in a marked fashion. Here was visible evidence that Soviet philosophers genuinely wished to make contact with the best natural scientists in the country in order to continue to try to overcome the legacy of Stalinism in philosophy.

Frolov was helped in his endeavor to modernize dialectical materialism by the presence in the late sixties and early seventies of a group of like-minded philosophers in the Institute of Philosophy of the Academy of Sciences, including its director, P. V. Kopnin; the historian and philosopher of science В. М. Kedrov, who had in the immediate post-World War II period made an unsuccessful similar effort; the philosopher of physics M. E. Omel’ianovskii and several other researchers in philosophy, including E. M. Chudinov and L. B. Bazhenov. While these scholars did not all agree with one another, they were united by the wish to avoid the infamous «dialectics of nature» approach that had, in the previous generation, often led to infringements on scientific research in the name of philosophy. The reformers of the sixties and early seventies wanted to concentrate on specifically philosophical questions, and leave the content of science to the natural scientists.

One of the most influential of the more sophisticated dialectical materialists’ works on biology was a book entitled Genetics and Dialectics published byI. T. Frolov in 1968. Frolov criticized the whole concept of «Party science,» firmly stating his opinion that politics concerns only the philosophical interpretation of science, not the evaluation of science itself. He criticized those conservatives such as Platonov who had not, in his opinion, yet seen this distinction.Second, Frolov tried to begin the process of reconstructing an intellectually tenable Marxist philosophy of biology out of the shambles left by Lysenkoism. He drew attention to legitimate philosophical problems of interpretation in genetics: the problem of reductionism, the problem of determinism, and the nature of heredity. He referred to the works of E. S. Bauer and Ludwig von Bertalanffy as examples of interpretations of biology that had similarities to dialectical materialism and that, therefore, should be further explored.

Frolov believed that the most important philosophical question in biology was that of reductionism, or the relation of the part to the whole. According to a strict reductionist, the characteristics of an organism can be entirely explained in terms of its parts. Thus, a reductionist would explain life in physicochemical terms. It was around this question that Soviet discussions of dialectical materialism and biology in the late sixties and seventies turned.

In Frolov’s opinion, dialectical materialism allowed one to have the advantage of studying both the part and the whole, of approaching biology both on the level of physicochemical laws and also on the more general biological or «systems theory» level. Frolov wrote that dialectics «defines a dual responsibility: On the one hand, it opens the way for complete freedom for the intensive use of the methods of physics and chemistry in studying living systems; on the other hand, it recognizes that biological phenomena will never, at any point in time, be fully explained in physiocochemical terms». The quantity-quality dialectical relationship had traditionally been interpreted by Soviet Marxists as a warning against reductionism, and Frolov continued to emphasize that warning.

By the seventies Soviet genetics as a science was well on its way to recovery, but not without continuing problems. The underlying issues of the Lysenko affair did not entirely disappear, however, especially in publications about philosophy and politics. Indeed, the seventies witnessed a regression, compared to the late sixties, in the degree to which science was free from political and philosophical fetters.

I. T. Frolov, the innovative editor of Problems of Philosophy, continued to attack Lysenkoite and Lamarckist viewpoints in his journal, and this message was often read to be a criticism of the nurture point of view as well. In a 1972 article, Frolov reminded his readers that Darwin had once said, «Heaven save me from the absurd Lamarckian ‘striving for progress.’. . .», and Frolov referred to the sad period in the history of Soviet genetics when «false attempts were made to give certain special conceptions and theories a broad ideological and socio-ideological character, which gave birth to the myth about ‘two genetics.’ «

I. T. Frolov was eager to get scientists and philosophers to talk together. The conversations on «the biological and the social» which he organized were extremely frank— so much so that the complete transcripts have never been published. Nonetheless, several summaries and descriptions of the debates have appeared. In addition, Frolov collected dozens of letters from individual scientists and citizens, the contents of which have also been partially described.

Despite their effort to be tolerant of divisions of opinion, in step with the atmosphere of the early post-Lysenko period, many of the philosophers present were shocked to hear A. A. Neifakh, a biologist, assert that not only were humans dramatically different in their intellectual and artistic abilities, but that Soviet authorities should use these findings of science in order to breed superior individuals.

The Harvard University entomologist E. 0. Wilson published his noted bookSociobiologyin 1975, at a time when discussions over nature and nurture in the Soviet Union were building to a crescendo. The book attracted considerable attention from Soviet reviewers and authors.

I. T. Frolov, a leading reformer among Soviet philosophers, was more restrained on the subject of sociobiology. He described sociobiology as «weak, even hopeless,» but he also said that it contains «interesting observations and conclusions.» Its primary flaw, he continued, was that it failed to understand that «the specific characteristic of man as a biosocial being is that his transformation into a ‘superbiological’ essence basically frees him from the influence of evolutionary mechanisms.»But as late as 1985 Frolov continued to display some sympathy for Wilson’s views. In a debate with Soviet philosophers who were critical of comparisons of man to other animals, he observed that only about one percent of the genetic information in human beings differs from that in chimpanzees, and he continued that Soviet biologists, just like the sociobiologists in the West, must investigate the significance of this small difference.»

“You can criticize the sociobiologists all you wish, but they are making an audacious attempt at decisive research investigations. . . . We must carry out similar research projects,” — I. T. Frolov wrote in 1983.

Soviet philosophers in the eighties began to pay much more attention to biomedical ethics and genetic engineering. The most prominent of them was I. T. Frolov, who devoted most of his research to these issues. His interpretation of genetic engineering was rather interesting, differing from that of Soviet natural scientists. …He sharply differed with Baev’s view that genetic engineering is just one more technology that can be used either for good or evil. Molecular biology and its applications raise social and ethical problems that are so intense, observed Frolov, that we can justifiably speak of «a new stage in the development of science.» This is a stage in which we must see that «science and scientific-technical progress are not a panacea for all ills. The danger has emerged of the development of certain directions in scientific-technical progress which directly and indirectly threaten man and humanity.» Frolov had obviously retreated from the optimistic Promethean scientism that characterized so much earlier Soviet writing on science.

According to Frolov, «Modern biological knowledge has posed a series of questions which concern the innermost foundations of human existence and affect the basis of science.» The ideological issues are «intertwined with the very ‘body’ of science, and are not something external to it.» Therefore, human genetics cannot be considered a purely scientific question; it is «inevitably included in a sharp philosophical, ideological struggle.» Thus, while Baev was arguing essentially that Soviet molecular biologists could go about their business as usual, Frolov said that the current situation was novel and required a new approach.

The possibility of the conscious and widespread application of genetic engineering to human beings in the future (even in ways that seem morally offensive now) cannot be excluded. On the other hand, maintained Frolov, it would be a great mistake to make such an effort now. For the time being, all eugenic ideas and all proposals to engineer a better human species should be rejected. The reasons, he said, are twofold: the science of genetics is still too incomplete and, even more important, power in the world is too unequally distributed. Even if the science of genetics were nearly perfected, continued Frolov, so long as some classes of people enjoyed many more privileges than others, the widespread use of genetic engineering would inevitably lead to the strengthening of elites and to the exploitation of the underprivileged. At some far future date, however, the question of improving the human species should be raised again; we should leave it to the people of that time, said Frolov, to decide the question, relying on what is anticipated to be their much better science of genetics within a just communist society.

1 — Loren R. Graham “Science, philosophy, and human behavior in the Soviet Union”. New York, Columbia University Press, 1987.

Toshitada Nakae

Remembering the Philosopher Ivan Frolov

Ten years has already passed since then. It was the evening of December 28, 1990. Moscow. We were walking across the snow-covered Red Square to the Kremlin Palace, where the President’s study was. Five years ago M.S.Gorbachev was elected the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee; more than one year before he became the first President of the USSR and really made a historical revolution by putting an end to the ”cold war”. By that time I had become the President of “Asahi” and was going to get an exclusive interview with this man

It goes without saying, neither Michael Sergeevich nor we could imagine that a year later the Soviet Union would break up, and Gorbachev would hand over the reins of government to B.N.Eltsin, President of Russia. We were happy then to have an opportunity to listen to Gorbachev firsthand, talking thoroughly for about two hours about the grounds of his philosophy. He was the man, who promoted with inspiration new democratic thinking in the home and foreign policy, where the ideas of “perestroika” (restructuring) and “glasnost” (openness) were the major components. Thus nothing prevented us to admire the aurora borealis of the last night of the leaving year and the dawn of a New year’s morning on our way back home when flying over the vast Siberian land.

During the years of my work as Editor in Chief of “Asahi” and later as its President I have met a dozen leaders of the global politics, but that meeting with the USSR President has impressed me most greatly by its content and the scope of Gorbachev’s personality as well. The organiser of our meeting and of the interview was Ivan Timofeevich Frolov, Editor in Chief of the newspaper “Pravda” at that time, he did his business displaying warmth, skills, and care. Up to now the idea does not leave me that Ivan Timofeevich was the nearest adviser and best friend of Gorbachev — the person, who at the end of the 20th century managed to change significantly the course of history.

In connection to this, I can’t help saying that the Gorbachev’s concept of “new thinking” remarkably reminded me of the ideas I had heard from Frolov at our meeting that occurred almost at the same time. This concept was announced by Gorbachev right before the end of the“cold war” in 1989 and presented modern world as not the two civilisations striving to destroy each other but as a single one, where the human values and free choice have a top priority.

In the latest years, Frolov as one of the best contemporary philosophers working for the Academy of Sciences was successfully engaged in investigating the paradigm of the modern world on the threshold of the 21stcentury and a new millennium. I was yearning in turn for obtaining the results on his studies, which would become for me an invaluable textbook of new thinking … But suddenly the bitter, terrifiing news about his death came.

Now I am sitting and looking at the large colour photo taken on the notable day of the interview with M.S.Gorbachev. The late President of “Asahi” — Mr. Muneyuki Matsushita (that time its Editor in Chief), who died last year is to the right of me in the photo. Frolov is next to Gorbachev, he also passed away last year. As it often happens the bitterness of loss and sorrow is added to my pleasant recollections. Ivan Timofeevich died unexpectedly during his research trip to one of the six ancient capitals of China – Hanjow — in the car, which just drove into the city. Before his death he only managed to wisper the name of his beloved wife — Galina, who was accompanying him on that trip.

Marco Polo called Hanjow the most beautiful and luxurious city of the world, and it might be that Frolov, who had managed to enjoy and admire its beauty before his death, not simply died, it was his ascension.

Bai Tzyui (Bai Letyan), a great Chinese poet, who was once the governor of Hanjow, in his famous poem “The song of everlasting sorrow” described the parting of the emperor of the Tan Lee Luntzi’s dynasty from his beloved wife Yan-Yuihuan. The lovers swear: “and if we happen to meet in Heaven, we shall become two inseparable birds, whose wings are drawn to each other at their each flapping, if on the earth, we’ll be a two-trunk pine, whose crowns are so close and the root is common”.

May be some day I would also reside in Heaven. Then I would find Ivan Timofeevich and would be able together with him to comprehend step by step the philosophy of the universal harmony of mankind.

VladimirA.Yadov

Man with a Capital “M”

Ivan Frolov was far from being an ordinary phenomenon in the social science of Russia. I have been lucky to be, at different times, his friend, colleague, or sometimes a stiff opponent. Some remarkable features distinguished Ivan Timofeevich among others.

He was undoubtedly a man of great personality. In the former Soviet times, bearing in mind the “structures” where Ivan worked, it meant much to be oneself, viz. a person with firm, progressive scientific and moral views and principles. Strictly speaking, it is to these few people to whom the country, its society and science owe their development, changes, and, probably, the progress itself (for nobody knows in advance how progressive the consequences of the reformers’ activities might be).

Ivan launched an absolutely new philosophical journal, which became something like Tvardovsky’s “Novy mir” (New World), i.e. the centre of freethinking and deep analysis of the social problems we faced at that time. The discussions in the journal were focused on the questions of keen interest, and the number of its subscribers probably doubled.

Ivan became the founder and the leader of an absolutely new for that time scientific trend, stating that Man as an individual and Homo Sapiens should appear in the centre of social knowledge or as some say nowadays, “of discourse”. It was a drastic turn in philosophy (i.e. the turn to the philosophical anthropology — the trend that was then alien to the official viewpoint) and in social sciences as well. Human being itself, and not a “state-society” was considered to be the major issue of philosophical and social knowledge. A new textbook on philosophy edited by I. Frolov and published in the perestroika period became a great event in the social life of the country.

He managed to unite the researchers of social and humanitarian sciences and those engaged in natural sciences, not in words, but in the joint Academy’s programme “Man”, where they worked together performing intensive studies; I feel happy I was actively involved in that work. Unfortunately, the collapse of the Soviet Union ruined this wonderful project.

Ivan Frolov represented the “brain centre” for restructuring barracks socialism into the socialism with a human face. Who knows, if the project succeeded (despite the antagonism, fight, and ambitions of the future Russian politicians and the conservatives from the CPSU), we would probably live in another and a better country, which would still remain one of the greatest states in the World.

I worked with Ivan Timofeevich over a new CPSU programme, which entirely changed the ruling party making it parliamentary and social-democratic. But the Plenum of the party’s conservatives turned down the programme, thus having signed the death sentence for the party itself. Today the political life in Russia is lacking this particular centre of ideas which, in fact, is mostly claimed by the majority of the Russian population.

At the same time Ivan Frolov had some distinctive features, which I did not appreciate. For instance, one cannot call him a compliant person. Sometimes he “cursed out” in the situations, when a common decision or position could be found. But this trifle cannot be characteristic for such a prominent scientist and human as Ivan was. Perhaps it even sets off the monumental figure of our friend and comrade.

For the last few months before the tragic event we mostly argued. It happened so that on the day of Ivan’s death, which occurred in China, I arrived in Shanghai. Pan-Dauei, my former post-graduate student, was involved in linking the Chinese services and the Russian consulate on that tragic occasion. Some time later Pan recalled the warm words that Ivan used when speaking of me – Pan’s scientific supervisor (although the day before, in Moscow, we “crossed” arguing as usual).

I do believe that such giants of Russian intellegencia (saying without exaggeration) as Ivan Frolov, actually affected the fate of Russia in science, as well as in its civil life. Thus to end these notes with such trivial and common words as “The memory of him …..” would be nonsense. This is just the truth; it is a social fact.

Mikhail S. Gorbachev

A Great and Worthy Man

My acquaintance with Ivan Timofeevich Frolov began long before we met in person. Perhaps his first “business cards” for me were the latest issues of the journal “Voprosy Philosophii” (Questions of Philosophy), which he headed starting from 1968. We were not only the subscribers to the journal for many years, but what was more important, we were interested in it as the readers, because Raisa Maximovna taught philosophy, sociology, and ethics and always displayed her interest in the Moscow and international discussions.

The years when the journal was under the leadership of Ivan Frolov, were not favourable to develop the public thinking. The Kosygin reforms were actually rolled up in this country. The forces of the Warsaw Treaty member-countries were brought into Czechoslovakia as a reaction to the “1968 Prague spring”. In fact, the period called “stagnation” was beginning in the former Soviet Union. Nevertheless the main philosophical journal managed to keep and even to improve its public and scientific position. This relates, in my opinion, to a wide scope of methodological and social problems of science and engineering development. By his scientific research and work in the journal Ivan Frolov made a great contribution to the public and scientific rehabilitation of modern genetics, which for a long time was disparaged by Lysenko’s supporters as a pseudoscience that in turn caused much damage to our science in this fundamental, vitally important field.

My personal meeting with Ivan Frolov took place in Moscow. Ivan Frolov was a man of principle as to his scientific and civil views and position and I was much impressed by this. He upheld them no matter whether the academic or party circles were pleased or not.

After the 1985 April CPSU Central Committee Plenum it became necessary for the social scientists to face the needs of real life, to begin the unbiassed comprehention of the new problems related to the development of the country and the world. Naturally, the journal “Communist”, a theoretical and political publication of the CPSU Central Committee should have set the first example. Its former leaders, however, were unable to perform this task, they were all “in captivity” of dogmatic stereotypes. In 1986 the Central Committee of the party appointed Ivan Frolov Editor-in-Chief of the “Communist”. Under his leadership, new topics and problems of keen interest were discussed and many new authors were involved in cooperation. But the main thing was that real life with its current events was traced on the pages of the journal, the breath of new and fresh thinking became tangible.

Quite a few new names appeared. There was, for instance, Tatyana Zaslavskaya among the authors. Her fundamental and brave sociological research was a new word in science and in party’s publications as well.

I remember what a great event it was when the materials of the Issyk-Kul Forum were published in the journal. Many distinguished persons met at the Forum: Arthur Miller, Alexander King, Olvin Toffler, Piter Ustinov, Federiko Major. Chingiz Aitmatov was its initiator and spiritual organizer. The Forum was held in October 1986, soon after the Reykjavik meeting. Nuclear threat, ecological problems, and deficiency of the moral criteria in the world’s politics were discussed there. Lenin’s idea, which was forgotten before, about the priority of the interests of the social development over the class’s interests appeared in the “Communist”; I reminded of that at the meeting, where I tried to ground the priority of universal human values in our nuclear-missile century. The publication drew a wide reaction in the former USSR and abroad. On the whole, the fact that the “Communist” raised the issue of the priority of universal human values was interpreted by some readers as revelation and by others — as heresy. But nobody was indifferent.

Ivan Timofeevich worked much over the problems of re-novating the socialism, of developing the public consciousness, of introducing complex approach to the study of modern human problems in their variety and intricacy. The wide range of his knowledge and scientific interests together with his political principles and views made me invite Ivan Frolov to work as the Assistant of the General secretary of the CPSU Central Committee and afterwards to recommend him as the Editor-in-Chief of the newspaper “Pravda” and the Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee.

After the XXVIII CPSU Congress I.T.Frolov still being Editor-in-Chief of the “Pravda” was elected a member of the party’s Politburo.

I highly appreciated his convinced devotion to the democratic reforms. Ivan Timofeevich always sounded courageous and impartial when protecting the reform course against any sort of politicians’ attacks — whether these were hard-liners or “ultrademocratic reformers”. Frolov could be sometimes rather “incovenient” or pretty sharp. I remember him speaking at different party forums and the Politburo meetings, when the situations were rather critical. It was unforgettable. We had to protect and to promote our reform policy constantly struggling with “left” and “right” radicals, who acted parallel, but actually were together in their striving for disruption of the democratic and restructring process, policy of renovation, reforms and the country’ unity. The “perestroika” opponents used all the means – from treachery and plots to obvious demagogy, promising to turn Russia into one of many developed and prosperous countries in two-three years. The results are well known. The “perestroika” process was disrupted, the final aim was not reached. But the positive results achieved in these few years, viz. “glasnost” (openness), freedom of speech, religion and conscience, new opportunities for the personal initiative, alternative elections, ideological and political pluralism, freedom of exit and travelling abroad, openness of contacts and communication with people all over the world, and many other democratic advantages – all these enable us to go on moving to real renovation and strengthening of democracy in our country, to asserting of self-respect of the Russian people.

Bearing in mind all these I want to say some kind words in memory of Ivan Timofeevich Frolov.We had friendly relations right up to his death about which I deeply regret. I have always deeply respected Ivan Timofeevich. He was a big and outstanding person, a real man. Solid. Educated. Man of principles and courage. Very open and sincere. I do believe Prof. Ivan Timofeevich Frolov has not completely used his scientific and civil potential. However, the things he has managed to do in science and in his life, undoubtedly deserve respect and admiration.

I recall with gratitude the years of my work with this great and worthy in every respect Man.

Lev N.Mitrokhin1

Life and Destiny

The philosophical thought and perhaps all humanities in Russia are unquestionably indebted to Ivan Frolov, the late Academician, for his services and for the very fact that they could survive the deadly embraces’ of Stalinist dogmatism and, nevertheless, went on revealing results that are highly appreciated by our colleagues all over the world.

One could point more specifically: from the mid-Sixties all events of noticeable significance in philosophy of our country, be they foundations of new perspective directions of scientific research, the achievements of the Voprosy Filosofii Monthly journal, the revival of the activities of the Russian Philosophical Society, new prospects for research programs (cooperation between philosophers and natural scientists, elaboration of global issues, the project «Genome of Man»), or the personnel reshuffle and large scale pedagogical innovations (e.g., the textbook Introduction to Philosophy,TV’s Philosophical Talks, publication of a book collection of religious philosophers of the Silver Age, to mention but a few, — all that had direct strings of connection with the imaginative and resolute support from Ivan Frolov himself.

He achieved those results both by his own research work and publications (his book Genetics and Dialectics, issued in 1968, became one of the decisive episodes in overcoming the rigid dogmas of official philosophy, as well as his well-thought-out organizational work in all high Party posts he assumed. At that period he occupied a number of posts — starting with that of Editor-in-Chief in theVoprosy Filosofii Monthly to the Member of Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the CPSU.

But at the end of the century the deviousness of History became apparent. It was just six months only that had passed since we celebrated the 70-th birthday of Academician Ivan Frolov: on this occasion his colleagues and friends lavishly and gratefully spoke about his impressive achievements as a scientist, as well as about prospects for their further fruitful cooperation.

That is why the news of his death was taken as absurdity, one could not be reconciled with, for it broke the very supporting pillars of our philosophical edifice. As for myself, I experienced a very strange stroke of emotion.

Being aware of the irreversibility of what really happened, I could not grasp its full meaning, while my friends and colleagues also intimated the same kind of feeling to me. Even now, when I enter my work place — the Institute of Philosophy — I still hope to see again a familiar figure of my old friend. I do not hasten either to call it a mysticism or resort to some other reasoning, but I am sure that a lot in his versatile and somewhat solid, somewhat contradictory personality, has always been and will forever remain mystery even to me, who in the period of 1948-1953 was a student in the same academic group with Ivan Frolov and Galina Belkina, his wife, at the Department of philosophy, Moscow State University, and ever since the routes of our lives have been constantly interwoven.

What kind of person was Ivan Frolov? What made it possible for him to fulfill such an immense work, and why is it so hard to reconcile ourselves with his passing away? One cannot understand a lot of facts in his biography if the most important thing is ignored: Ivan Timofeyevich Frolov was a notable, outstanding personality; early in his life he had set himself great and noble aims and pursued them with ;in amazing consistency, invariably keeping safe a sense of his own professional dignity.

In the situation of a rigid ideological dictate, which reigned at that period. , the path traversed by him was especially thorny, for he was a young editor-in-chief of a leading philosophical monthly (I mean theVoprosy Fiiosofiijournal., where he began his career of a well-known scholar) at the time when self-sufficient, independently-minded personalities were subject to constant persecutions. I don’t mean frictions and debates around some articles to be published. There was one very simple thing which made the journal’s existence socially dubious and suspicious in the eves of ideology guardians, for the system of partocracy, despite all its assurances that the creative thinking was not only permissible, but even desirable, was not really in need of the philosophy itself. Philosophy as a supreme form of culture, which plays the role of intellectual critical instance and, by its very classification, is incompatible with any manipulations «from above», resisted any spiritual despotism in anything, whatever it could be: assessment of German classical philosophy; worldview conclusions on the basis of latest discoveries in modern physics; characteristics, given to renowned writers and philosophers of the West. Since Voprosy Filosofii was entirely devoted to expert research in that kind of metaphysical matters, it became utterly impossible for any author here to be intricate or vague, to guard oneself with formal arguments or circumlocutions, to resort to a kind of professional slang or references to some specific author’s situation. So, the Editor-in-Chief was always running the risk of finding himself under an ideological suspicion.

Ivan Frolov himself always stressed the point that he was inspired by an idea to found a new professional journal, elaborating on the most fundamental problems of modern philosophy. And he was ideally fit for such a role to play. Even in his student years at the Moscow State University he worked as an editor for the USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House. Later he worked as an executive secretary at the Voprosy Filosofii Monthly. Especially precious for him was an experience gained in the World Marxist Review in Prague and later on — in the capacity of an assistant to a Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU, which enriched him with a detailed knowledge of intimate procedures of formation and dissemination of the Party ideology. Finally, there were long years of systematic studies in biology, which required strictly scientific methods and responsibility of a researcher and, at the same time, confirmed his feeling of independence from official dogmatism, enabling him to maintain daily contacts and mutual understanding with the most gifted natural scientists — a factor largely determining the profile of the journal.

I would not like to dwell too much on those radical (and largely well known) changes, that took place in the journal with Ivan Frolov coming there. I want to recall just one instance. Now it is difficult to imagine what the introduction into the Journal new Editorial Board of such people as P. Kopnin, A. Zinoviev, B. Grushin, V. Lektorsky, Y. Zamoshkin (and, perhaps, your humble servant as well) signified, to say nothing of the appointment of Merab Mamardashvili as a Deputy Editor-in-Chief. All of us became official heads of departments, who actually controlled both the choice of themes of articles to be published and the very process of their discussion at the editorial board meetings.

Certainly, our undertakings were not always successful. All of us were facing ideological pressures. But the main line of defense was held by the Editor-in-Chief himself, and one can easily imagine how exhausting could have been our visits to the CC CPSU («Old Square»), how much humiliation one could experience in futile efforts to defend one or another «dubious» material from the philosophically ignorant «curators», who insisted on our «recognition of mistakes done». But, in spite of everything, Ivan Frolov could manage a principal thing: in the years of severe hardening of political censure, the central «ideological» journal did become a symbol of free thinking and intellectual freedom, comparable with those of NovyMir magazine (and that was openly recognized).

From aside, the life history of Ivan Frolov may be seen as a Christmas story of a lucky guy, who all of a sudden and in spite of any obstacles made a vertiginous ascension to the heights of political power and academic recognition. Moreover, his public figure record was open for anyone to observe. His drive in defending his stands and actions was well known, and his image of a person «very sure of himself», authoritative and even willful, was rather a stable one. His sharp sense of humor of his own making could shock even very high-ranking companions. It is only now that I little by little begin to realize how superficial are such observations and how abundant was his life in painful doubts and hurt feelings. Along with his personal «star hours», there were also minutes of doubt and sufferings — as a price to be paid for those high purposes (not those of ascending the career-ladder or reaching places of honor as such, but his life’s ideals), which he had so early and consciously formulated for himself — a price for the self-confidence in the pursuit of his self-imposed mission in the academic field.

His childhood was arduous, for, starting at the age of twelve, he had to earn his daily bread by exhausting manual labor. He got married very young and had to earn extra to keep his family. I remember his first family apartment — a small room in a communal compound, where he settled down with his wife Galya and daughter Lena. And further on — a constant work, mastering new skills and fields of knowledge, as well as his amazing purposefulness. When I try to understand the source of his internal fortitude, there always comes to my mind an image of a truly Russian man, closely linked by invisible threads with his country, its soil and organically absorbing what is habitually called the Russian spirituality. And that is not just a literary image.

Ivan Frolov avoided confessional overtones. It is only in his last interviews that there surfaced traces of innermost spiritual emotions, and an image of his native small town of Dobroye was coming to the fore. When sharing his impressions of Solzhenitsin’s story of Matryona’s Homestead, he wrote: «My cousin Tatyana’s homestead was exactly like Matryona’s one and of people like her. But it is a special and very intimate topic». Dobroye occupied a special place in Ivan’s heart. He used to speak about it with an inexpressible love and visited it as soon as there was a chance to do that (I happened to accompany him there several times). The population of that «former defense line town with a castle» (as he used to call it), situated on the bank of the Voronezh River, flowing into the Don River, initially consisted of the state owned peasants, free from serfdom and carrying out defensive duties on the state border. The spirit of free enterprise and Cossack liberties reigned there. Today one can find traces of fortification towers, formerly well-to-do homesteds: corn-chandler’s brick shops which were ruined long ago, cobbled roads, neglected stores, several ruined churches (Frolov happened to help restore the main one of them). A striking beauty of the Middle Russia belt of lands, that could be adequately depicted in literature only perhaps by M. Prishvin and G. Paustovsky: winding streams, transparent long-abandoned river-beds, emerald-green water meadows. In this freedom-loving milieu the family traditions of the Frolovs were being formed. They remained dear to Ivan all his life through: it was there that he had roots of his moral strength and inherited sense of dignity.

I know how selfless and sincere he was in dying to bring to life the idea of humane and democratic socialism. Therefore, he perceived the disintegration of the Soviet Union as a treachery one and his own personal tragedy. But as we now recall, he was steady in preserving his own dignity and did all in his power to create and nurture his favorite child, he dreamed about for many years — the Institute of Man.

I think that Ivan Frolov was aware of the significance of his own missionary service to philosophy and the impossibility of its optimal realization. Hence — the hidden bitterness, that was evident in his last interview when he spoke about the death. He cited unforgettable words of Bulgakov’s Master, that expressed bottomless torture of his soul: «Gods, my Gods! How sad is the Earth in the evening!..». And very soon the circle of Ivan Frolov’s own life was closed. What is left for us is to work for the sake of triumph of our Common Cause and be grateful to the Providence for the opportunity to have known this outstanding and courageous man.

1 — Lev Mitrokhin – Academician of RAS, Editor-in-Chief of the Journal Social Sciences